The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Court recently ruled that an employee who follows his supervisor’s instruction to falsely report that he did not work any overtime hours still can pursue an overtime claim. It reversed a decision from the Western District of New York, which had dismissed the claim because it did not believe the employee could prove how many hours of overtime he had worked.

Greg Kuebel was a Retail Specialist for Black & Decker (U.S.) Inc. He filed class action lawsuit against Black & Decker, claiming the company’s overtime pay practices violate the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and the New York Labor Law (NYLL). Specifically, Mr. Kuebel claims Black & Decker violated the law by failing to pay him for the overtime hours he worked but did not record on his timesheet — in other words, his “off-the-clock” overtime hours.

Greg Kuebel was a Retail Specialist for Black & Decker (U.S.) Inc. He filed class action lawsuit against Black & Decker, claiming the company’s overtime pay practices violate the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and the New York Labor Law (NYLL). Specifically, Mr. Kuebel claims Black & Decker violated the law by failing to pay him for the overtime hours he worked but did not record on his timesheet — in other words, his “off-the-clock” overtime hours.

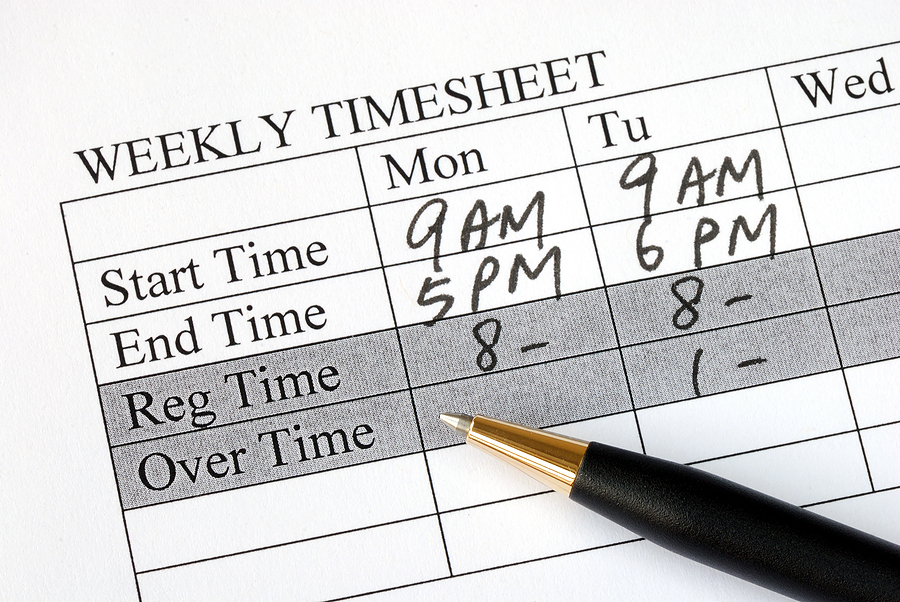

Black & Decker’s official policy required Retail Specialists to accurately record their hours on timesheets that they submit to their managers. There was no official Black & Decker policy which prohibited Retail Specialists from working, recording, or being paid for overtime. However, Black & Decker expected its Retail Specialists to finish their work in a 40-hour work week.

Mr. Kuebel alleges it was impossible to finish all of his work in 40 hours per week, and as a result often worked overtime. However, he did not list any overtime on his timesheets, and therefore was not paid for his overtime hours. Mr. Kuebel explained that he falsified his timesheets because his supervisors instructed him not to record more than 40 hours of work per week because the company could not afford overtime. Mr. Kuebel testified that to the best of his memory he worked more than 40 hours almost every week, and averaged between 1 to 5 hours of overtime per week. After Mr. Kuebel told his supervisor that he had been falsifying his timesheets, Black & Decker fired him for poor performance, dishonesty, and falsification of company records.

In Kuebel v. Black & Decker Inc., the Court explained that to prove an overtime case under the FLSA, an employee has to prove he was not properly paid for working more than 40 hours in a work week, and his employer either actually knew it or should have known about it under the circumstances. To prove the amount of overtime pay to which he is entitled, an employee needs enough evidence to show the amount and extent of the overtime he worked. However, he does not have to prove the amount of overtime he worked with definiteness, and can prove his overtime hours through an inference. Accordingly, the Court ruled that when a company’s time records are inaccurate or inadequate, the solution is not to penalize the employee by denying him any legal recovery.

To summarize, an employee can win an overtime case if (1) he proves he actually worked overtime and was not properly paid for it, and (2) he has enough evidence to show how much overtime he worked through a reasonable inference. An employee can meet this burden through estimates based on his own recollection. This can be true even when the employee admittedly falsified his own timesheets, at least where the employee’s falsification was based on an instruction from a manager or supervisor. That is because it is the employer’s duty to maintain accurate time records for its employees, and employers cannot delegate that duty to their employee. Once an employer knows or has reason to know an employee is working overtime, it cannot deny compensation simply because the employee failed to properly record or claim his overtime hours.

Continue reading

New Jersey Employment Lawyer Blog

New Jersey Employment Lawyer Blog

Earlier this year, a New Jersey Judge refused to file the terms of a settlement agreement in an overtime lawsuit under seal. Specifically, Judge Jose L. Linares of the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey ruled the employer had not overcome the strong presumption of public access to the terms of settlements in cases under the Fair Labor Standards Act (“FLSA”). The FLSA is a federal

Earlier this year, a New Jersey Judge refused to file the terms of a settlement agreement in an overtime lawsuit under seal. Specifically, Judge Jose L. Linares of the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey ruled the employer had not overcome the strong presumption of public access to the terms of settlements in cases under the Fair Labor Standards Act (“FLSA”). The FLSA is a federal